Short Term Respite: Clarity, Contradictions, and the Cost of Caring

October 21, 2025

Author: Jon Anning, Lead NDIS Consultant

Recently NDIS’ new Short Term Respite (STR) guidelines were released and a few things got my attention. I couldn’t help reflecting on what they reveal about how the Scheme values (or perhaps undervalues) the role of informal carers.

It’s not all bad. In fact, there’s finally some long-needed clarity about what respite actually is: a structured break for informal carers, not a mini-holiday or a funded trip to the movies. The guideline neatly shuts down the age-old debate about whether NDIS should be paying for mini golf or popcorn. On that front, its positive.

What’s Changed and What It Means

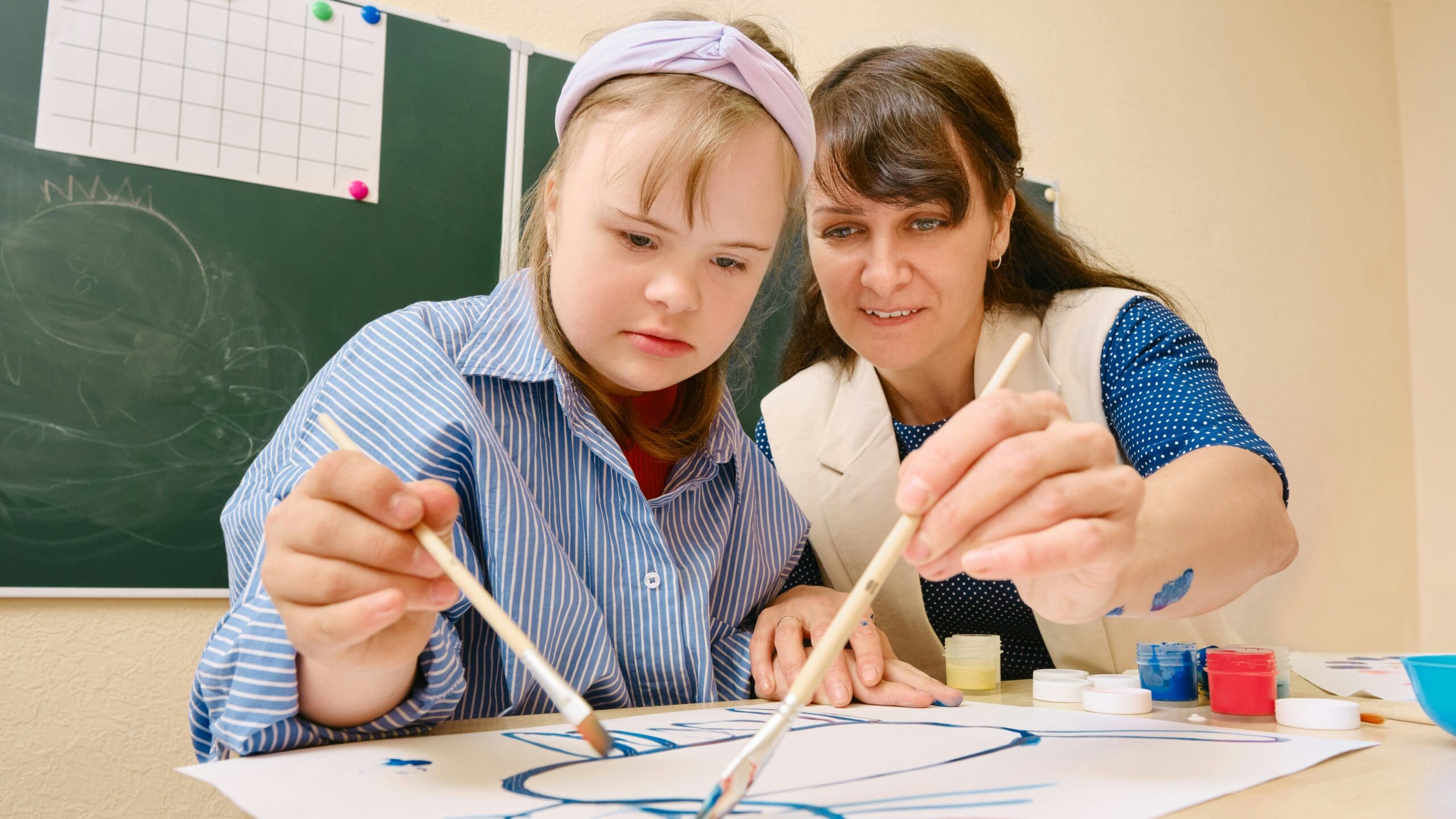

The updated NDIS Short Term Respite guideline clarifies how respite can be funded and under what circumstances. In essence, respite remains positioned as a break for informal carers, not a standalone support for participants.

- Duration: Up to 14 days at a time, 28 days per year.

- Eligibility: You must rely on informal supports for over 6 hours a day of active, disability-related care.

- Purpose: To sustain existing informal support arrangements — not to replace family care, mainstream services, or everyday parenting.

- For Children: The guideline explicitly states the NDIA will only fund STR for children in “exceptional circumstances.” Parents are expected to provide “age-appropriate care” (eg toileting, settling to sleep, and emotional support) just as any other parent would.

- Exclusions: STR is not for holidays, meals, or general family relief. It must relate directly to disability support needs, be value for money, and align with NDIS goals.

The document frames respite as a means to preserve the informal caring arrangement, not as a proactive support for participants’ or families’ wellbeing.

The Human Reality Beneath the Policy It Means

On paper, the guideline sounds reasonable, a tidy model where carers get a brief break and participants continue being supported. But beneath that neatness lies a subtle tension: a policy designed to sustain informal care rather than to sustain families.

By reinforcing “reasonable parental responsibility,” the NDIA continues to apply a neurotypical and non-disabled lens to parenting. What’s “age-appropriate” for a typical child may be impossible, unsafe, or emotionally exhausting for a child with complex disabilities.

For example, a 10-year-old with autism who doesn’t sleep through the night or needs active toileting support is not a child whose parents can “just manage.” Yet under these rules, families in exactly that situation will likely find their respite requests declined – until they are in crisis.

This creates a perverse incentive: families must demonstrate near-collapse to qualify for these services. That may save money short-term but ultimately drives burnout, breakdowns, and out-of-home placements – which are exponentially more costly to the Scheme and traumatic for families.

Evidence vs. Intention

Research on carer fatigue consistently shows that early, predictable respite reduces long-term system costs. Carers Australia and multiple state carer surveys found large a majority of carers delayed seeking formal support until they’re at breaking point, citing administrative barriers and narrow eligibility definitions. The NDIS Review (2023) promoted preventative approaches to make the system work better – precisely the opposite direction of this update.

The guideline’s focus on “exceptional circumstances” for children and its strict framing of parental duties will likely reduce access to STR, particularly for families of children with autism, intellectual disability, or complex behaviours.

In practice, that means:

- More reliance on exhausted informal carers rather than funded supports.

- Delayed requests until families meet the “risk of placement breakdown” threshold.

- Short-term savings but higher long-term costs, as families burn out and participants enter residential or out-of-home care.

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions”

If the NDIA’s goal is to prolong the time participants live with family, this policy may undermine that very goal.

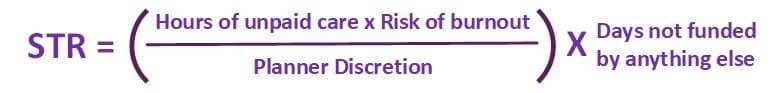

The “Formula” for Funding Respite

The section on how your STR budget is calculated reads like something straight from an excel spreadsheet with formulas that never works. The planner must consider:

- Hours of informal support each day

- Paid supports already in place

- School holiday gaps

- Shared vs individual ratios

- Intensity of needs at different times of day

- Duplication across Core budgets

Add a dash of “local availability” and a pinch of “value for money,” and you get something like this:

It’s hard not to feel that the more complicated the calculation, the more likely the outcome will under-fund what families actually need.

Contradictions and Confusion

Then there’s the small matter of contradiction.

The Disability Support Worker Cost Model – the NDIA’s own pricing bible – includes meals and incidentals in the daily STR rate when the setting is comparable to a hotel or group home. Yet, the new guideline suggests that providers may not include meals in their daily rate, and can’t include them in an individual service.

So, which is it?

If a provider offers meals, must they now itemise and deduct them from the daily rate? And if they don’t, will participants pay the same rate for less service?

It’s this type of confusion which can make the relationship between planning, service delivery and claiming a task fraught with danger.

The Hidden Rules Behind the Rules

The guideline technically includes everything you’d expect from the reasonable and necessary framework, it says the NDIA must consider whether STR will help sustain informal care, whether carers’ wellbeing is at risk, and whether the support prevents breakdown of living arrangements.

The problem is you need to wade through the paragraphs of reasons why it won’t be funded to get there. This guideline is administratively neat but may be emotionally tone-deaf.

Final Thoughts

The Short-Term Respite guideline delivers clarity on paper but confusion in practice. It defines the edges of respite funding so tightly that the human need it’s meant to serve risks falling through the gaps.

If the NDIA really wants to prolong the time people with disability live with their families, and reduce long-term costs to the Scheme, it needs to view respite not as an exceptional expense, but as core infrastructure for sustainable informal care.

Families typically don’t need respite because they want a break from their child – they need it because they want to keep going. An effective short-term respite policy would view respite as an investment in long-term stability, not an “exception” reluctantly granted at the point of exhaustion.

Copyright ©2025 BONORIGO, All Rights Reserved. | Site by Ignite X

Connect with us

+614 0400 30 1818

Contact Us

Bonorigo acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional custodians of the land on which we work, the muwinina (mouwee-nee-nah) people of nipaluna (nip-ah-loo-nah), now known as Hobart. We honor their enduring connection to land, sea, and culture, and recognise that sovereignty was never ceded. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and extend that respect to all First Nations people.